The college basketball playoffs in the United States have just ended. Basketball sets the theme for the apparent resolution of a longstanding issue involving photography, and by implication many other areas of design.

If without permission, you re-use someone else’s photograph, you may be looking at paying for copyright infringement. This is assuming that you somehow got hold of a digital copy of the photo.

But what if you do not literally copy? What if you look at the photograph and decide to set up a shoot that will duplicate it closely? Is your photo, clearly intended to look like the other, an infringement? An urban legend states that it is. The three leading cases, however, say that it is not. This differentiates photography from music, where copyright infringement has been found where one piece sounded somewhat like one written by a different composer, even where there is no proof that the “copier” knew of the existence of the first piece of music.

In the three cases involving a “copied” photograph, including the one I’m about to discuss, the copier most certainly did know, and did intend to steal the concept. In the most well-known previous case, Skyy Vodka, whose signature blue bottle is quite attractive, was in talks with a photographer about an advertising campaign. He provided them with three sample shots that they liked very much, but they could not agree on a price to use them and in any event the photographer insisted on a licensing arrangement rather than a total transfer of rights. The company then found another, cheaper photographer, to whom they showed the first photographer’s work, saying, this is (wink, leer) the sort of thing we would like. The cheaper photographer obediently produced a series of very similar shots, which Skyy used in advertising. The first photographer then sued for copyright infringement.

He lost. And it took him ten years. The first judge, ignoring all the skillful lighting and background effects, ruled that the photographs were uncopyrightable because too much of them depended on the vodka bottle, which of course the photographer had no claim to. Having determined that no copyright existed, he had no need to rule on whether the second photographer’s work infringed it.

An appeals court, however, decided that the photos could be copyrighted and told the first judge to consider the infringement question. He did, and concluded there was none. He seemed to agree that one independently-shot photograph could theoretically infringe another’s copyright, but he said that in the vodka bottle situation “highly similar” was not enough, even granted that the second photographer was trying to copy the first one’s work. The two photos needed to be “virtually identical” for the plaintiff photographer to win, and of course they were not.

A second appeals court agreed. Here is the opening of their opinion: “This long-running litigation is fundamentally about how many ways one can create an advertising photograph, called a ‘product shot,’ of a blue vodka bottle. We conclude there are not very many.” This was in 2003, ten years after the original photographs were taken.

In other words, the rationale for requiring that the two be “virtually identical” is that otherwise too many legitimate attempts to portray the bottle could be challenged. That ruling left open the question: what if there is no doubt that the concept of a photograph was copied, but the photograph was so creatively arranged that nobody would ever come close to it by accident?

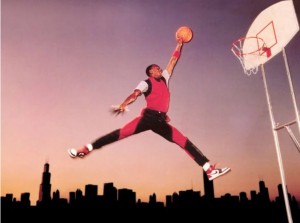

Just such a photo was taken in 1984. The photographer’s contribution was to instruct a college student named Michael Jordan, wearing his USA Olympic sweats, to assume a ballet-like pose while soaring to dunk toward a basket that the photographer had constructed to seem impossibly high. The whole scene is outdoors, not on a basketball court. It appeared in Life magazine and aroused the interest of Nike, which paid the photographer $150 to use it in a slide presentation.

Shortly thereafter, Nike decided that it needed a picture like it for its own marketing purposes, but Jordan had to be wearing Nike shoes, and also the attire of his new team, the Chicago Bulls. So they hired Jordan to duplicate his pose, leaping outdoors toward a basket that was at a more reasonable height than in the original, and hired a photographer to shoot at the same unusual angle. This new photo was used over and over to promote Nike’s fabulously successful Air Jordan line of shoes. Furthermore, they derived a bitmap image, a solid silhouette, from the Nike photo. This was used as the logo for the fabulously successful Jumpman line starting in 1987.

When the photographer saw the new Nike picture, he threatened to sue, so Nike paid him $15,000 for the rights to use its own image for two years, although apparently they continued to use it for a while afterward.

Sales of the Jordan-branded lines were in the billions of dollars. The original photographer thought it would be useful if he shared in some of the largess, so in 2015, more than 30 years after the photo was taken, he sued Nike for copyright infringement. The federal judge hearing the lawsuit threw it out without a trial, stating that neither the second photograph nor the logo was an infringement as a matter of law. In doing this, he relied not only on the vodka-bottle case, also on an earlier one involving a student of mine, who specializes in photographing babies. She had done a beautiful magazine spread in the 1980s, featuring nude babies apparently floating in air, carefully lit and tastefully presented.

A midwestern hospital thought that this would be just the thing for one of its brochures promoting its neonatal care facilities. It therefore contacted my student about purchasing the rights. Before anything could be finalized, however, objections were raised that her photographs showed the babies’ genitalia, which would no doubt be shocking to the hospital’s audience. They therefore hired another photographer to take extremely similar photographs, more discreetly posed, of different babies.

My student sued, and lost. The court acknowledged that the hospital’s intent was to copy her work, but informed her that designs, concepts, and lighting methods are not copyrightable, only her specific implementation with specific babies. So, the result again: the allegedly infringing photo needs to be virtually identical to the original or the first photographer is out of luck.

The case that was just decided is more complicated because, among other things, the same individual was photographed each time. Still, there is no question that the following things cannot be copyrighted in and of themselves.

*The particular pose, unusual as it is.

*Michael Jordan dunking a basketball.

*Michael Jordan playing basketball outdoors.

*The angle the photographer chose for the shot.

*A basketball hoop much greater than the regulation height.

However, if enough of these elements are included simultaneously, then copying all of them could, according to the court, result in a copyright violation. The Nike photo copied four of them. The logo didn’t copy any of them: it’s an unidentifiable silhouetted figure, based only on the Nike photograph, where the pose is slightly different than the original. Therefore, all the judges hearing this case agreed that the photographer had no valid claim against the logo.

But the Nike photograph itself? Well, in addition to the lower basket, the background is totally different, as is the clothing. Jordan is older and the pose is, understandably since it is taken mid-air, not quite identical to the original. There’s a colorful sunset on the left, whereas in the original the sun is not colorful and it’s on the right. Jordan is much larger compared to the background in the Nike shot. The original focused the lighting on the ball, while the Nike version focused on Jordan’s face.

For two of the three appeals court judges, that’s enough difference. Their holding: if a nonexpert viewer can readily tell the two photos apart, then there’s no copyright infringement. Nike wins.

The third judge agreed with the others that the original photographer had no claim to the logo, which was where the big money was. As to Nike’s photograph, though, he would have sent the case to a jury to decide whether the two images were “substantially similar”.

Since the ruling wasn’t unanimous, I thought it might attract the attention of the Supreme Court. But no, they did not wish to take the case, which means it is now over, ending as the other two did with a loss for the photographer.

The lesson? Suing someone on the basis that a photograph, though admittedly not a direct copy of yours, is too similar, is not going to succeed even if it’s clear that the other photographer was intending to pirate whatever creativity you put into it and hope that his work would be mistaken for yours. All these photographers lost a lot of time and money chasing rainbows.

On the other hand, it is expensive to get sued, even if you eventually win. These three copiers at least tried to make a deal with the original photographers. That made their defense a lot simpler, and would be a wise choice for any photographer or designer in the same position.

{ 0 comments… add one now }